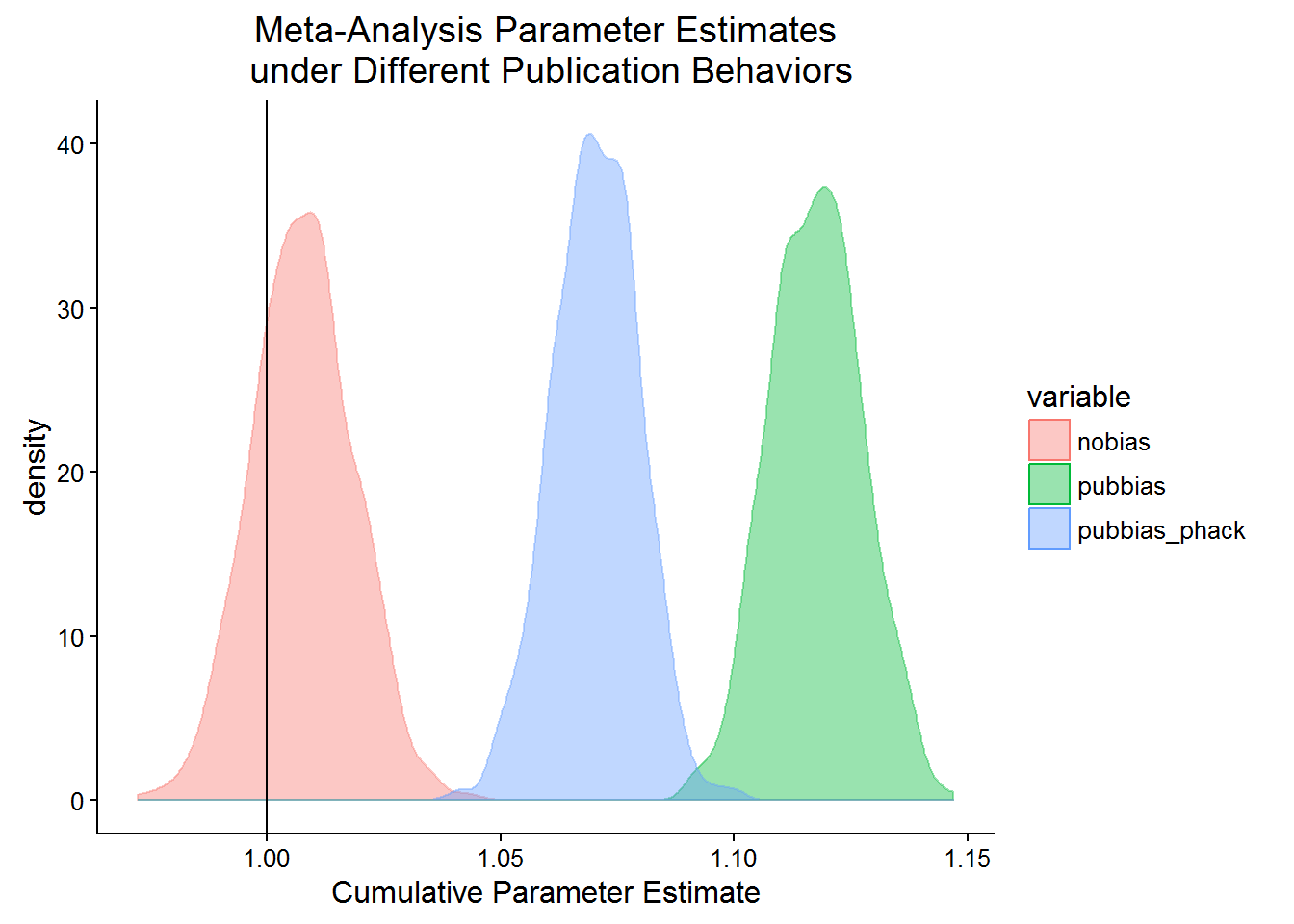

Most people would agree that “p-hacking””, the art of getting a p-value just below 0.05, and publication bias both hurt the accumulation of knowledge. We end up with data hidden in subfolders of discarded laptops and estimated effects biased away from 0. However, their effect on meta-analyses is not additive. In fact, if we take publication bias as given, p-hacking actually might reduce the bias in naive meta-analyses.

Let’s say that there is no p-hacking but there is publication bias. In this situation, only results that are statistically significant are published, and each individual study provides an unbiased estimate of the population parameter. When these studies are aggregated (for now let’s consider their simple mean), the aggregate estimated parameter will be biased away from 0. Now let’s imagine a world where there is also p-hacking. There are many ways to p-hack, but let’s consider the case where one is changing model specifications to increase the size of the parameter of interest.1 In this case, many results that are just large enough to be published appear in the literature. These estimates will have a mean closer to 0 than the mean of the statistically significant results because they have been p-hacked to be just barely significant. Therefore, this will bring the cumulative estimate of the population parameter towards 0, thus mitigating the bias from publication bias. Given publication bias, p-hacking actually reduces the bias in our estimates of the population parameter.

To demonstrate this further, I will use an example in R. First let us set up a population where the true parameter is 1 but is realized with some error. Then I write a function cumulative_est that computes three cumulative estimates—one with no bias, one with publication bias, and one with publication bias and p-hacking—of the population parameter following 500 experiments. First, it runs experiments 500 times, sampling from the population, estimating the mean and the p-value corresponding to the t-test that the parameter is not 0. From these experiments, we take the mean of these individually estimated parameter values to produce a cumulative estimate of the population parameter under the three aforementioned conditions.

We operationalize publication_bias as the proportion of non-significant parameter estimates that end up being published. Then p_hacking_level as the amount of bias researchers are willing or able to induce in their parameter estimate to get a statistically significant result and p_hacking_success is the number of p-hacking attempts that work. I also assume that p-hackers stop p-hacking once they creep their confidence interval just north of 0 and thus their estimates are biased upwards by $0$ minus the lower bound of the confidence interval.

# The population to sample from, with a treatment effect of 1 with some random error

treat_pop <- rnorm(10^5, mean = 1, sd = 7)

# Function that takes a sample size and returns the mean and p-value

estimate_treat <- function(n) {

samp <- sample(treat_pop, size = n)

out <- t.test(samp)

c(out$estimate, out$p.value, out$conf.int)

}

# Function to run n_exps experiments and compute a cumulative estimate under different

# scientific regimes.

cumulative_est <- function(n, n_exps, publication_bias, p_hacking_level, p_hacking_success) {

experiment_estimates <- sapply(rep(n, n_exps), estimate_treat)

ests <- experiment_estimates[1, ]

pvals <- experiment_estimates[2, ]

lower_bound <- experiment_estimates[3, ]

# Find estimates that are able to be p-hacked

phacked <- (pvals > 0.05 & (lower_bound + p_hacking_level) > 0)

# Only a proportion of these succeed

phacked_success <- (phacked & (cumsum(phacked) <= floor(sum(phacked) * p_hacking_success)))

# Get the remaining insignificant estimates

insignif <- (!phacked_success & pvals > 0.05)

# Publish the first #insignificant * (1 - publication_bias)

insignif_pub <- (insignif & (cumsum(insignif) <= floor(sum(insignif) * (1 - publication_bias))))

# The published estaimates are all of the significant estimates, (1 - publication bias)

# proportion of insignificant and non-p-hacked estimates, and p-hacked estimates

# The p-hacked estimates are the original estimates + enough bias to get the lower bound

# of the confidence interval to be just above 0.

published_ests <- c(ests[pvals <= 0.05 | insignif_pub], ests[phacked_success] - lower_bound[phacked_success])

return(mean(published_ests))

}Now I use Monte Carlo simulations to show how the cumulative estimate of the population parameter will be less biased under p-hacking and publication bias than just under publication bias. The first case, nobias is when there is no publication bias and no phacking. In the second case, pubbias, only 1 out of every 40 insignificant results is published. In the third case, pubbias_phack, can add up to 0.2 to their effect and get published 19 out of 20 times. Note that they only bias their parameter estimate by just enough to pull the lower bound of the confidence interval above 0. In this case, we also allow 1 in 40 of the remaining insigificant, non-p-hacked results to get published.

sims <- 1000

set.seed(20160122)

nobias <- replicate(sims, cumulative_est(n = 400,

n_exps = 1000,

publication_bias = 0,

p_hacking_level = 0,

p_hacking_success = 0))

set.seed(20160122)

pubbias <- replicate(sims, cumulative_est(n = 400,

n_exps = 1000,

publication_bias = 0.975,

p_hacking_level = 0,

p_hacking_success = 0))

set.seed(20160122)

pubbias_phack <- replicate(sims, cumulative_est(n = 400,

n_exps = 1000,

publication_bias = 0.975,

p_hacking_level = 0.2,

p_hacking_success = 0.95))So, given publication bias, does p-hacking improve cumulative estimates of population parameters?

library(knitr)

kable(matrix(c(1, mean(nobias), mean(pubbias), mean(pubbias_phack)), nrow = 1,

dimnames = list(NULL, c("True parameter", "No bias", "Pub. bias", "Pub bias + p-hacking"))),

digits = 2)| True parameter | No bias | Pub. bias | Pub bias + p-hacking |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1.11 | 1.06 |

Indeed it appears that it does! Let’s plot the 1000 simulated cumulative estimates of the population parameter.

library(ggplot2)

library(reshape2)

plot.df <- melt(data.frame(nobias, pubbias, pubbias_phack))## No id variables; using all as measure variablesggplot(plot.df, aes(x = value, color = variable, fill = variable)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.4) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 1) +

ggtitle("Meta-Analysis Parameter Estimates\n under Different Publication Behaviors") +

xlab("Cumulative Parameter Estimate") +

theme_classic()

Feel free to take the code and play around with the parameters.

-

In fact, if p-hacking is done by choosing one-sided tests instead of two-sided tests after seeing the data, the attenuation in bias will be even greater because the individual experiments will not produce estimates biased away from 0. Only their p-values will change! ↩